That God may welcome into his peace all who have died due to the pandemic and console their relatives and all who mourn them. Lord hear us.

That God may welcome into his peace all who have died due to the pandemic and console their relatives and all who mourn them. Lord hear us.

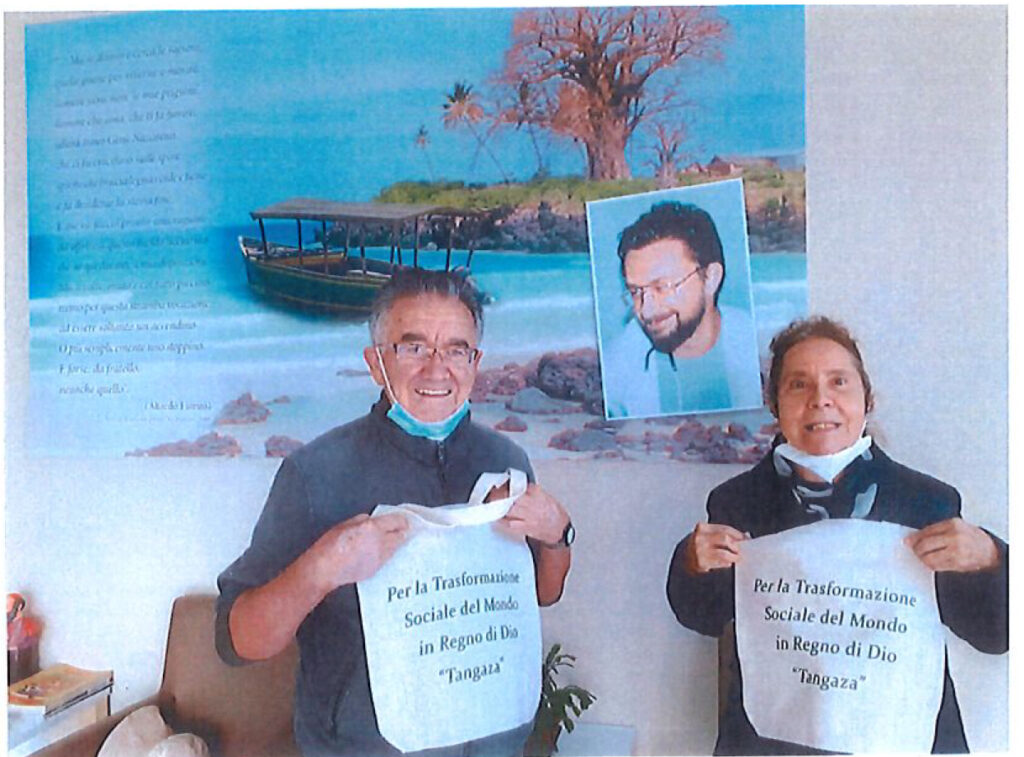

We share with you an inspiring letter for Christian commitment in politics and economics shared with us by Father Francisco Pierli and Sister Teresita Cortés.

Very dear friends and Colleagues,

Thanks to God, that after a long spell of silence we are now in position of joyfully communicating with you from a beautiful part of Italy where we Combonis have an institution for the recovery of sickly and elderly confreres. It is the so-called “Centro Alfredo Fiorini” dedicated to a Comboni Brother who was murdered in Mozambique during a Social Mission.

We are writing this letter to underline that our communion continues and hopefully will increase since the health of Fr Pierli is improving.

We took the opportunity to visit the House and the Museum of the great Italian Politician Alcide De Gasperi. In eight successive coalition governments he served as Prime Minister and he was always clearly inspired by the Catholic Social Teaching. He was one of the Founders of the European Union together with Konrad Adenauer from Germany and Robert Schuman from France. We did that visit to the House and Museum of Alcides De Gasperi as a pilgrimage. We are interested in the above mentioned Politicians because all of them and especially De Gasperi, were ready to invest themselves to the utmost to transform the Civil Society according to the Gospel values. They were Statesmen, with a vision of the future, totally committed to regeneration – rebuilding, after the Second World War, of their own respective countries socially and economically and to unite them into a federation as a seed of a greater United Europe. De Gasperi’s Cause of Beatification has been already started. “A Politician looks at the next election, but a Statesman looks at the next generation”. (Alcide De Gasperi).

They inspire us with their commitment, to re-interpret our Christian faith in Politics and Economics: in Parliament, in the State House and in Social life. In spite of the difficulties they met, they managed to penetrate the world of politics and in the field of economics with the Christian values elaborated in the Documents of the Social Teaching of the Church.

May their example and intercession help all of you Kenyan and African Politicians to be at the service of your people, actually people God has entrusted to you, for the liberation of the plague of the society, and for the construction of unity and communion at National and Continental level.

Fraternal greetings and best wishes! With our prayers for you,

Fr Francesco Pierli MCCCJ – Sr, Teresita Cortés Aguirre CMS

In the chapel of St. John Paul II in Krakow LMC Bartłomiej Tumiłowicz was officially sent on a mission to Africa.

Bartłomiej Tumiłowicz took up the challenge of being a lay missionary on the continent, from where “the spring of the Church will come”, as the patron of his parish, St. Pope John Paul II, said.

In his homily, bishop Robert Chrząszcz referred to the Gospel passage about the Apostles wanting to sit next to the Savior in His kingdom (Mark 10,35-45), noting that in order to get there, one must first put on the robe of humility during earthly life: – Do these words really turn the world upside down? Actually, it is not. It’s just getting it back in order. Jesus often broke established patterns of thought in order to introduce the order of the Gospel, which was the guarantee of true happiness. He wants to free us from the desires that enslave us. Today He wants to convince each of us that our greatness is not about domination and possession.

The hierarch indicated, for example, the patron of the parish, who with love undertook the great responsibility that was upon him: – “Whoever would become great among you, let him be your servant.” The patron of our parish community, St. John Paul II the Great. And we know that his greatness was not that he was pope, but he was great because he had an attitude of service. He wanted to serve man in the position where God had put him. Because the attitude of the service does not mean hiding in the shadows, not taking up positions or running away from activity. There is also no need to change work to a more servant one.

The clergyman emphasized that this humility helps us achieve great things. Referring to the task undertaken by the lay missionary, he remarked: – We know and believe that Bartlomiej is not going there to reign in order to suddenly be able to call himself a great missionary, or to consider himself important because “I will be a missionary”. He is going there to serve. Therefore, this mission is great, very important. The more we have this will to serve, to give ourselves to others in our hearts, the greater we become in God’s eyes.

The bishop said about the goals that the missionary has before him: – That is why today we remember St. John Paul II the Great and those other great saints who, through their service and their gift, showed greatness in simplicity and love for God. Today we also pray for Bartlomiej that good God will accompany him, that he will understand well this spirit of service, which will be very necessary for him there in his missionary work. That he could open the hearts of other people to Christ. But starting to open his own heart.

CLM from Poland

In this missionary month the Church encourages us again to be witnesses.

We, as missionaries present in various continents, are witnesses of a humanity that wants to live fully and be happy.

We are witnesses of the inequalities that are spread over all continents, of the accumulation by some who do not want to look towards their brothers and sisters, as well as the difficulties of many to have the most basic things.

But above all we are witnesses to the generosity and solidarity that exists among people. When we share the difficulties we also open ourselves to share the way out of it, to share the possibilities of improvement, to share what we have and above all what we are.

As humanity we need human warmth, one from another. This pandemic has forced us to physically separate ourselves at many times to protect ourselves, but we know that nothing is as comforting as an embrace. In an embrace we express closeness and complicity with each other’s lives, with each other’s suffering, with each other’s joys.

We witness how generosity emerges in the midst of difficulties. Of course, we are overwhelmed by the miseries to which so many people are subjected, but we cannot be paralyzed by this vision. We must not close our eyes but act.

But we cannot reduce the person to his or her difficulties and forget how much we have experienced in so many countries and with so many cultures. The generosity of those who offer everything they have, the openness of their homes to those who come from abroad, the joyful welcome of those who feel they are foreigners, the capacity for recovery and resilience that makes people go out every day to look for a better future for their families, the effort to study and learn every day….

That is why in this month when we turn our eyes to the mission we want to be witnesses of the God of Life, of how his Spirit becomes present and fills with Life the communities of the peripheries of the world. We want to be witnesses of Jesus of Nazareth who walks every day with those who need him most, even when sometimes we are not even able to perceive His presence.

We encourage all of you to take a step forward and commit ourselves to life. Life in abundance that Jesus brings to all humanity.

Let us each do our bit.

We cannot but speak about what we have seen and heard. Acts 4,20. Alberto de la Portilla, CLM

Together with all the missionaries of the world we thank the Lord for the opportunities he gives us of serving the neediest and we pray that we may always be able to do it with love. Lord hear us.