“Comboni – since he believed in the unity of the human race and in the fact that the Gospel must be addressed to everyone – adopts an attitude of prophetic demystification of that form of cultural racism…” (Prof. Fulvio De Giorgi, Consiglio di Direzione di Archivio Comboniano).

Contextualisation

Any up-to-date reflection on the “Plan” of Comboni that is not simply historical but something that is spiritual, pastoral and missiological (made from the point of view of faith, of belonging to the Catholic Church and of Comboni ‘offspring’), must start with contextualisation, without adopting a level of interpretation that is direct and unmediated, as if it were a modern text. Actualisation must avoid the danger of a certain sort of over-simplified actualising fundamentalism; this, at best, would amount to trivialisation or, at worst, serious distortion. No text of the period (not only those of Comboni) can be read without contextual filters: otherwise, for example, anyone who at that historical moment was against racism could risk to be seen today as a racist.

It is not simply a matter of translating the language of the XIX century into the language of today (using a method that is not simply one of historical semantics): even if just this understandable aspect indicates a much greater problem: that of the forms of cultural (and spiritual) continuity/discontinuity between ourselves and our Fathers and Mothers of the past, between our vision and theirs.

Comboni saw himself within the Catholic Church: but so do we, today. However, the Catholic Church is a living organism that is growing: it has therefore ‘grown’ with respect to the XIX Century. And this growth includes self-awareness: the ecclesial vision itself. We cannot, therefore, feel ‘perfectly comfortable’ in the attire of the nineteenth century: if we did, then this would mean everything was at a standstill, that Christianity was not living but dead, and that our task would not be historical but archaeological…

Actuality and prophecy

In short, it is clearly evident that the ecclesiological paradigm of Comboni, his ecclesial vision, was that of Vatican I and not that of Vatican II and that his culture, within which many aspects of his ecclesial vision were defined, was that of Lombardy-Venice of the XIX century and not of the XXI century. So, then, what does this (obvious) statement mean for our interpretation? Which are the traits of continuity, actuality and prophecy and which are those of discontinuity within which there has been progress (growth)?

The closer the cultural elements of Comboni are to the Gospel, the more continuity there is: the Church proclaims the Gospel of Jesus Christ as a proposal of a liberating covenant offered by God to the whole human race (which – and it was not so obvious then as it is now – implies the unity of the human race: there is only one human race and all men and women are sons and daughters of God, equal in personal dignity). To such an extent that, in the heart of Europe, there grew the new cultural form of racism. Comboni was alien and opposed to such cultural developments. Racism implies two essential elements: 1. Human races exist (usually reduced to three); 2. There are inferior and superior races. Comboni – since he believed in the unity of the human race and in the fact that the Gospel must be addressed to everyone – adopts an attitude of prophetic demystification of that form of cultural racism. Here, moreover, there is not only continuity but also a permanent actuality in this approach because, whether in an explicit or, more often, a dissimulated form, there still persist today racist visions that are capable of finding a place even in the ecclesial vision.

Discontinuity as growth

Cultural elements of discontinuity, instead, are those most closely tied to the specifics of mentality and thought of the time: ‘geographic’, ethnographic and cultural ignorance of the Europeans regarding many parts of the planet and many layers of humanity; the existence – therefore – of mythical fantasies and of common traditional places (including religious ones: such as the so-called ‘curse of Ham’) which filled these cognitive lacunae and which today may seem to be ‘racial prejudice’ (they were prejudices, just as we all have prejudices but not racial prejudices since they did not share – as I have already stated – in the specific elements of that cultural form).

Methodologically, it is essential to understand these differences so as to be able to see the reflection on the “Plan” of Comboni against the background of his ecclesial vision and his prophetic actuality.

Unity, utility e simplicity

If we adopt the racist view, we will hold that European civilisation is superior and therefore destined to dominate others: condemning them to ‘separate’ development (apartheid) or ‘civilising them’ from above and outside some aspects of them, the better to rule and exploit them for the purposes of the Civilisation held to be superior. In the “Plan”, Comboni adopts an opposite paradigm: that of the unity of the human race. In this framework, it is possible that some peoples (historically speaking, these were the Europeans, but they might have been others) are the first, due to historical coincidences, to accomplish achievements to be considered positive (e.g. writing, literacy, medicine, science or technology): these achievements are then made known to all, they are shared and made available to ‘regenerate’ all of humanity, to improve, in other words, real existence by diminishing all forms of suffering, poverty and injustice, for the purposes of common usefulness. But this ‘civilisation’ (‘the sharing of the achievements of civilisation’) is not to be imposed from above or from outside: if this were the case, even with the best of intentions, asymmetry and therefore a possible imbalance and dominance would be introduced. Civilisation/sharing is to be proposed and carried out from below and within, under the immediate leadership of the beneficiaries, without deceit or complicated mediations but in simplicity: only then is it ‘re-generating’ (intrinsically emancipating). The results, consequently, will be generating and generators, creative and innovating, autochthonous and original, not extrinsically similar (assimilated) to those of Europe, nor yet hostile to them: because they are the fruit of a fraternal encounter in which the good of all is sought and not an unbalanced encounter (a clash of cultures) in which the good of just one party is sought (the stronger one).

The presuppositions, therefore, of the ecclesial vision of Comboni in the “Plan” may be summed up in these still actual words-symbols of his: unity, utility, simplicity.

The approach of the Plan

Such an approach as that of the “Plan” is, effectively, all the more relevant today, in a world that is globalised and interdependent (much more than in the XIX century), because it indicates the only way forward for a unitarian but not uniform development of the human race, in a plan of non-violence and sharing, always respecting the others. The approach of the “Plan” demystifies two perspectives that make up, today, the two greatest dangers of dehumanisation: on the one hand the dynamics of unequal development, with a logic (like that of neo-liberalism) which tends to increase the claws of riches through communitarianism and xenophobic exclusion, rejecting the equality of rights and personal dignity; and, on the other, aggressive western culturalisation such as large-scale defoliation of all local culture, or universal standardisation or the ‘McDonaldisation’ of the world.

This approach of the “Plan”, which seems to be in prophetic harmony with the social teaching of the Church (cf. the actual indications of Pope Francis), even though formulated in a period in which the expression itself “the social teaching of the Church” did not yet exist, was, for Comboni, the consequence of an ecclesial vision that had to be rooted in the Gospel of liberation of Jesus of Nazareth. Even today, it is against the background of the Gospel that the Plan must be seen to best understand it and put it into practice in fidelity to the charism: this is an essential hermeneutic criterion for a modern interpretation of the “Plan”.

Consequently, some essential elements of the ecclesiological vision of the “Plan” (which at the time, were by no means held by the majority or taken for granted, although they could be seen in an important tradition of Propaganda Fide), appear prophetic and, even today, bearers of evangelical renewal: the Implantatio Ecclesiae as the founding of truly local Churches with local clergy; equality of race in all meaningful ambits, especially those of the spiritual and Christian life; the importance – ad intra and ad extra – of the Catholic laity.

The subject is broad, fruitful and rich in possible new developments – but here I can only make a brief reference to this – the matter of the pedagogical apparatus of the “Plan” which, in an original manner, combines different elements: the emancipating power of instruction for all; education as intellectual charity; the pedagogy of the oppressed.

An ecclesial vision that is harmoniously Unitarian

It is precisely the pedagogical apparatus that produces a harmoniously unitarian ecclesial vision – since it is unitarily founded on the formation of consciences – of evangelisation and human promotion: “The formation to be given to all the individuals of either sex who belong to the Institutes surrounding Africa must be characterised by the following goals: to impress and plant in their souls the spirit of Jesus Christ, integrity of behaviour, firmness of Faith, the principles of Christian morals, a knowledge of the Catholic catechism and the basic elements of necessary human knowledge.” (W. 826)

Prof. Fulvio De Giorgi

(Consiglio di Direzione di Archivio Comboniano)

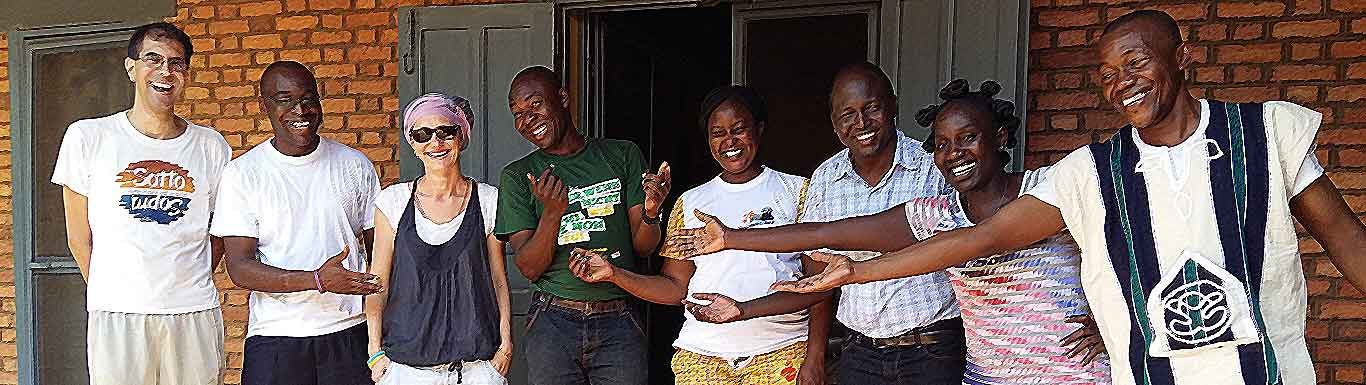

Three months has lasted our experience in London, in this process of intensive training before leaving for mission, where we worked to improve our English, and where we could know each other better and walk among us as a Community.

Three months has lasted our experience in London, in this process of intensive training before leaving for mission, where we worked to improve our English, and where we could know each other better and walk among us as a Community.