A commentary on Mk 14, 12-16,22-26: Corpus Christi solemnity, June 7th

The Corpus Christi solemnity -celebrated on Thursday in some places and on Sunday in others- is an excellent occasion to reflect and become aware of this great Christian reality. After having read the piece of Mark’s Gospel that the liturgy offers us today, I share with you three points of meditation:

1) To remember a loved person

1) To remember a loved person

As we grow in age, we tend to keep a set of “things” that remind us of people we love specially. We gather a set of memories that usually “materialize” (take “flesh”) in pictures or other objects that acquire for us a meaning and a value that go far beyond its physical value. It happens to me, for example, with my father’s cap; after his death I kept it as a very special and meaningful object. I look at it, I handle it on my hands, I cover my head with it… and all this makes me feel in communion with my father.

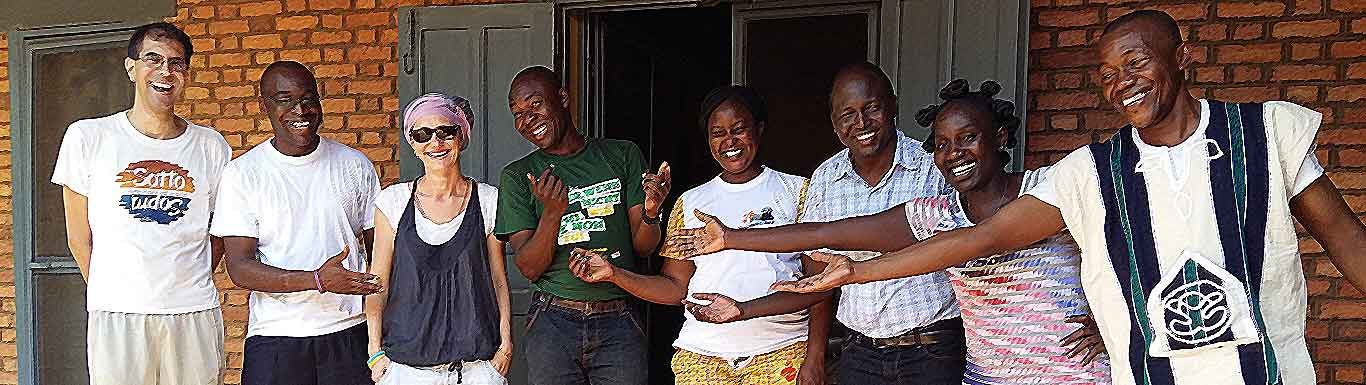

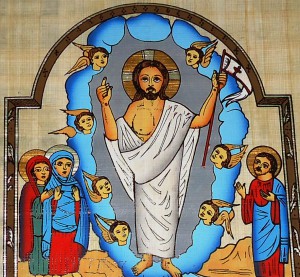

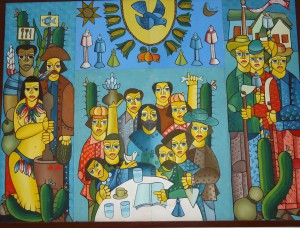

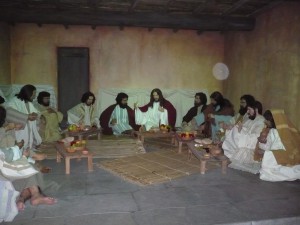

It occurs to me that something similar happened to the disciples after that last supper, when Jesus, before confronting his death, ate with them the Passover meal, broke the bread (real image of his broken body), passed the cup of wine (image of his split blood) and said words that sounded more or less like these: “Do not forget me, remain united, love each other, go on with the work of the Kingdom. I am with you to the end of the ages”. The disciple took seriously those gestures and words, as a testament of love, and kept them alive, generation after generation, up to our days. Now we are part of that sacred faithfulness to the body and blood of Jesus Christ.

The Eucharistic celebration is not a “heavy duty”, a clerical affair, a magic rite or any other similar false appreciation. To celebrate the Eucharist is to be in communion with our Friend, Brother and Master Jesus and, in Him, enter in communion with the Father, enjoy His presence and renew the certainty of His love that nourishes us and pushes us to love and serve others, specially the most abandoned.

2) The best part is still to come

2) The best part is still to come

Jesus’ last supper is part of the Israel’s secular tradition. For Jews it was quite clear that God has acted in their history: liberating them from slavery, supporting them in the difficult crossing of the dessert, helping them to overcome the exile… All this was celebrated –and continuous to be celebrated– every year with the Pascal meal, as a feast of memory and hope. If God was with them in the past, his help will be there also in the future.

For us the Eucharistic celebration moves on the same lines: celebrating the memory of Jesus we renew our hope (in spite of our sins and failures) and our engagement for the future: Jesus was with us in the past, but He is with us now and He will always be in the future. In a sense, as we celebrate the Eucharist, we are sure that the best of our live is still to come; that, every day that passes by, we are approaching the Kingdom of God more and more.

3) The room in the upper floor

3) The room in the upper floor

To celebrate the Passover, Jesus needed a room in the upper floor… These words make me remember when Joseph was looking for a room in Bethlehem where Mary could give birth to his Divine Son… It seems that God cannot be born in our humanity, cannot be transformed into “bread and wine” without a place ready to welcome Him. As a matter of fact, it is quite difficult for a community to gather without a place for it (under a three, in a family’s living room, in a rural church or a cathedral), but , more than a physical place, God needs a human heart, a person, an open community, a family, a people… ready to welcome Him and accept Him. Only in that way, the miracle of His presence can happen. Am I this open person, where God can come and renew His Alliance with me and humanity?

Fr. Antonio Villarino

Roma