The mission of Dadim is located in the remote Borana zone in the far south of Ethiopia, near the border of Kenya. The name Dadim comes from “dakkaa diimaa” which means red stone and the origin is obvious after placing your foot on the bright red soil of Dadim for the first time. The road from Awassa until the turn off for the mission is relatively good because it is the main asphalt road that connects Ethiopia to Kenya. But the final 11 km to the mission takes 1 hour in a good 4-wheel drive during the dry season and becomes impassible in the rainy season. There are two priests here, Fr. Boniface from Kenya and Fr. Iede, from the Netherlands, and 3 religious sisters, Anila, Annie and Shirley, from India who together operate a parish, school, community centre and clinic. Fr. Iede has spent the better part of his life here in Dadim – he arrived in 1973 upon the request of the Borana Elders to establish the first education services in the region. He slept the first two years in a tent. Despite the Borana elders lack of formal education, they identified education as a priority and hoped that a higher educational level would prepare their children to cope better with the changes affecting the pastoralists as a group. After establishing the first school, the focus shifted to health and in 1981 the first healthcare services began. Dadim’s location was selected since it was in a “no-man’s” land located between the grazing areas and major water points of three pastoralists ethnic groups: Borana, Guji and Ghabra. This would mean that all three groups would peacefully have access to educational and health services with school children remaining in their surroundings and therefore in touch with their indigenous pastoralist life style.

The mission of Dadim is located in the remote Borana zone in the far south of Ethiopia, near the border of Kenya. The name Dadim comes from “dakkaa diimaa” which means red stone and the origin is obvious after placing your foot on the bright red soil of Dadim for the first time. The road from Awassa until the turn off for the mission is relatively good because it is the main asphalt road that connects Ethiopia to Kenya. But the final 11 km to the mission takes 1 hour in a good 4-wheel drive during the dry season and becomes impassible in the rainy season. There are two priests here, Fr. Boniface from Kenya and Fr. Iede, from the Netherlands, and 3 religious sisters, Anila, Annie and Shirley, from India who together operate a parish, school, community centre and clinic. Fr. Iede has spent the better part of his life here in Dadim – he arrived in 1973 upon the request of the Borana Elders to establish the first education services in the region. He slept the first two years in a tent. Despite the Borana elders lack of formal education, they identified education as a priority and hoped that a higher educational level would prepare their children to cope better with the changes affecting the pastoralists as a group. After establishing the first school, the focus shifted to health and in 1981 the first healthcare services began. Dadim’s location was selected since it was in a “no-man’s” land located between the grazing areas and major water points of three pastoralists ethnic groups: Borana, Guji and Ghabra. This would mean that all three groups would peacefully have access to educational and health services with school children remaining in their surroundings and therefore in touch with their indigenous pastoralist life style.

Walking into the Dadim Clinic today, after 30 years of development, we were quite impressed with the polished setup. We were however surprised to see that only 15 patients will come for treatment on any given day despite it being the main health centre in the area serving approximately 27,000 people. This is because the Borana people are largely pastoralists (semi-nomadic animal herders) and especially now during the dry season they are moving from place to place in search of food and water for their animals.

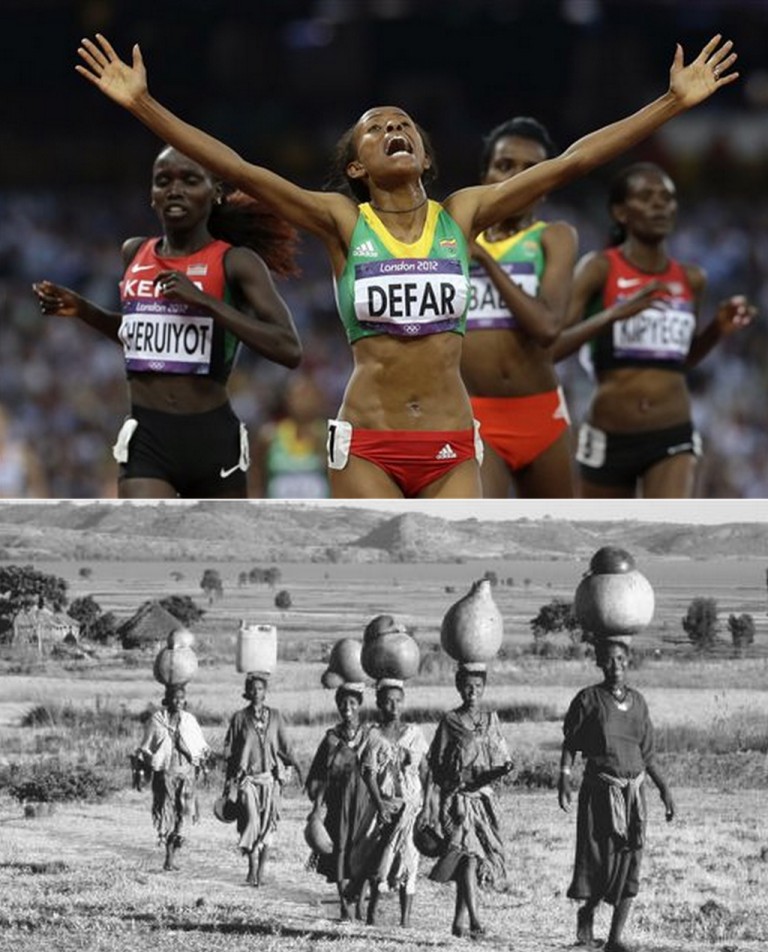

Cattle and camels are fundamental to their way of life. In the dry season the whole concentration of the Borana centers on water and grass – two vital resources for the maintenance of their herds and consequently their livelihood. The Borana have developed complex management systems and societal rules for the access rights, control and sustainable development of the two precious resources of grass and water. As the dry season causes sources to vanish, they pack up their simple grass houses and few possessions, and simply move closer to the last valuable sources like water bore holes and hand-dug wells. The Borana diet revolves mainly around milk – from cows, camels and goats. The annual cycle of rainy and then dry seasons can be seen in the physical appearance (and underlying health) of both the people and their herds. Both go from plump to withered, from vibrant to emaciated as the seasons roll on.

Given the pastoralist lifestyle, health care delivery is a challenge to say the least. The Dadim clinic remains as the central treatment hub, but the health care program involves a massive outward deployment into community based health care. For this reason three days a week the staff go out to find the Borana wherever they are – delivering anti natal care, vaccinations, and some limited acute patient care truly in the middle of nowhere! Actually, it is not in the middle of nowhere for the Borana (the clinic has a set of 15 health posts with a network of community health workers who mobilize people to the posts), but it sure feels like it is.

Given the pastoralist lifestyle, health care delivery is a challenge to say the least. The Dadim clinic remains as the central treatment hub, but the health care program involves a massive outward deployment into community based health care. For this reason three days a week the staff go out to find the Borana wherever they are – delivering anti natal care, vaccinations, and some limited acute patient care truly in the middle of nowhere! Actually, it is not in the middle of nowhere for the Borana (the clinic has a set of 15 health posts with a network of community health workers who mobilize people to the posts), but it sure feels like it is.

When we were visiting Dadim, we accompanied the sisters and staff out to one of these remote outreach health posts. It was an adventure to find the road (or rather make our own road) through the thorny acacia tree covered savannah. Nausea was the theme of the trip as the 4WD lurched up and down over the water-chiseled landscape. When it does rain here on the savannah, it rains hard – so hard that the parched ground instantly becomes a flood zone and this violent flow of water scars the land. On the drive we saw gigantic hares, tiny dik dik gazelles (the size of small dogs), beautiful zebras and of course lots of camels.

Finally we spotted our destination – a small collection of mud huts on the crest of a hill. We parked the car under the shade of a tree and began to unload little tables, chairs, record books, a cooler storing the vaccines and other supplies. We could see woman and children converging, ascending the hill from all directions. When some older children saw the Sisters they affectionately called out “Yoya!” which means I embrace you. There was one vacant mud hut which seemed suitable for children’s vaccinations, another hut for ante-natal care and the acute patient care would be provided from the back of the truck.

The Borana people here are completely different from the Sidama ethnic group with whom we work and live in Awassa. The Borana women wear vibrant clothes and large beaded necklaces, and have their sleepy sweaty-faced babies tightly wrapped in colourful fabrics.

The Borana people here are completely different from the Sidama ethnic group with whom we work and live in Awassa. The Borana women wear vibrant clothes and large beaded necklaces, and have their sleepy sweaty-faced babies tightly wrapped in colourful fabrics.

The women came from both near and far and stayed most of the day under the shade of the tree, laughing and chatting with one another. There was a public health nurse, a local Borana man, with us and at an opportune moment when all were gathered together he gave an ‘awareness creation’ lesson on HIV/AIDS which included sharing the benefits of voluntarily getting tested. Throughout the day, upwards of 150 women arrived for this ‘mobile’ clinic.

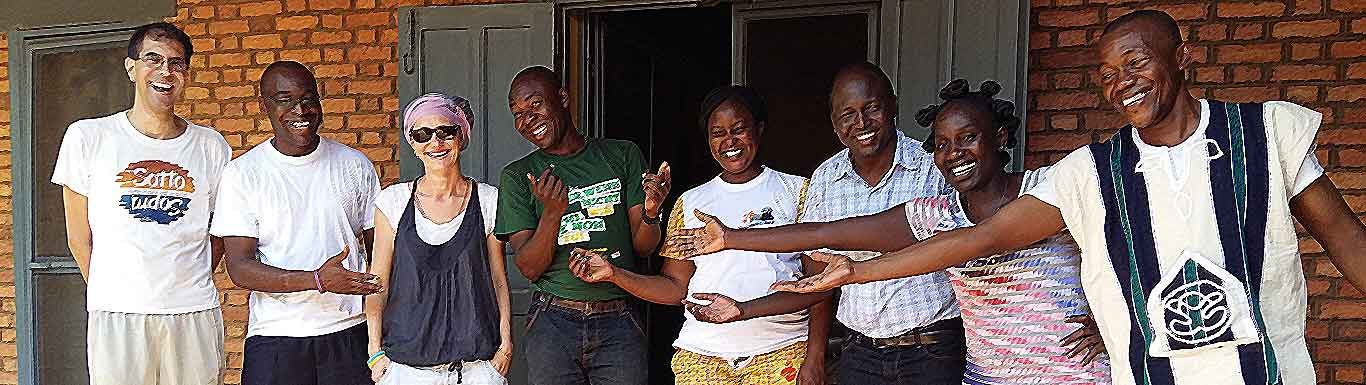

This kind of health care delivery is not without serious challenges, both practical, financial and clinical. Sometimes the sisters and staff end up travelling on very bad roads for up to 90 km, and then work in the heat all day, without proper lunch. Also, the costs of fuel, trucks and bonuses paid to staff make these trips very expensive. The health care quality offered through the remote outreach posts is low without a proper place to perform patient exams, limited equipment and without laboratory facilities. The Dadim clinic is working to evolve the health care model by training a network of health extension workers (such as Traditional Birth Attendants) who actually live in the Borana communities. They are also strengthening the services offered through the central clinic. Now after decades of supporting the local people to achieve higher education in healthcare, 20 of the 22 clinic staff are local Borana. That means that local Borana are serving their fellow people to work together to build stronger society. So as the pastoralist lifestyle inevitably changes, the Borana will be better equipped not only to navigate the change but help plot its course.

This kind of health care delivery is not without serious challenges, both practical, financial and clinical. Sometimes the sisters and staff end up travelling on very bad roads for up to 90 km, and then work in the heat all day, without proper lunch. Also, the costs of fuel, trucks and bonuses paid to staff make these trips very expensive. The health care quality offered through the remote outreach posts is low without a proper place to perform patient exams, limited equipment and without laboratory facilities. The Dadim clinic is working to evolve the health care model by training a network of health extension workers (such as Traditional Birth Attendants) who actually live in the Borana communities. They are also strengthening the services offered through the central clinic. Now after decades of supporting the local people to achieve higher education in healthcare, 20 of the 22 clinic staff are local Borana. That means that local Borana are serving their fellow people to work together to build stronger society. So as the pastoralist lifestyle inevitably changes, the Borana will be better equipped not only to navigate the change but help plot its course.

– Maggie, Mark and Emebet Banga, Comboni Lay Missionaries, Awassa, Ethiopia